This paper was presented to the Hawkesbury District Historical Society on the 200th anniversary of the Rum Rebellion (1808 – 1810) as the Society’s Australia Day address in 2008, at Pitt Town.

“Ready at All Times, at the Risque of Our Lives and Property”[1]:

The Hawkesbury Resistance to the Usurpation known as the Rum Rebellion

Introduction

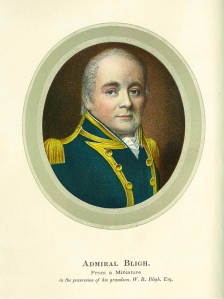

Tonight, on this 200th anniversary of the overthrow of Governor Bligh, I want to explore the story of those who opposed the Usurpers, and the price they paid, especially among the Hawkesbury settlers.

Setting the Scene: New South Wales in 1808

Firstly, I want to set the scene, and ask you to imagine a New South Wales that is very different to today. Sydney was the capital, and to the west were the impassable Blue Mountains. The colony’s population of about 8000 convicts, settlers and soldiers was spread between the two towns of Sydney and Parramatta, and the country districts of the Hawkesbury, Baulkham Hills, the Field of Mars and more sparsely The Cowpastures. Beyond the County of Cumberland there was also the remote penal station at Coal River, the Queensborough, Phillipsburg and Kingston settlements on Norfolk Island, and the newer settlements at Port Dalrymple and Hobart Town in Van Diemen’s Land.

The colony was largely maritime in its outlook: the principle highways were by river and sea rather that overland, significant economic activities centred on the seasonal sealing and whaling in the southern fisheries, and one of its major means of convict imprisonment were restrictions on convict labour in boat building and fishing. It probably seemed natural to many people that the governance of this ‘South Seas’ colony rested in the hands of a succession of naval officers, and that the seemingly unlimited powers of the early governors were not unlike those of a sea captain.

The Hawkesbury District was the most ‘inland’ settlement in the colony, and even it was frequently journeyed to and from by way of the river and the coast rather than the rough road to Parramatta. Boat building and maintenance were a feature of the district’s economy, which along with regular flooding suggests the importance of the aquatic environment even when far from the sea.

It was into this marine colony that Captain William Bligh RN arrived in August 1806 as the fourth governor of New South Wales. He immediately made his mark felt, not least by providing public assistance to the Hawkesbury settlers who had just survived their fourth devastating flood with great losses to their crops and stock, as well as houses, sheds, roads and even lives.

This then is the stage upon which the drama of the Rum Rebellion would be played out.

How others have seen it

I was probably first struck by the idea of a resistance to the Rum Rebellion a few years ago when I read HV Evatt’s 1938 history titled Rum Rebellion. In his introduction Evatt wrote of Governor Bligh exercising his authority in favour of the agriculturalists and poor settlers and against the wealthy traffickers and monopolists.

Evatt’s 1938 history of the Usurpation. Image Editions Books

Bligh has had over 200 years of bad press, but my objective tonight is not to try and rescue his reputation. Neither is it to look at the motives and actions of the Usurpers and the other chief protagonist, John Macarthur. Instead, I want to focus on the “agriculturalists and poor settlers” that Bligh apparently championed. Who were they? How did they show their support for him? How did they resist the Usurpation? What did it cost them?

Evatt provides a good coverage of the 19th century historiography of the rebellion[2]; and Brian Fletcher writing in 1968 covered the 20th century writings[3]. The Hawkesbury settlers have been cast as either hostile to the uprising and loyal to Bligh, or as worthless characters easily bribed to sign petitions. These points of view can be traced directly back to the opposing arguments advanced at the trial of one of the rebel leaders, Colonel Johnston, in 1811. There is also another view, in which the settlers and the loyalists resisting the Usurpers are simply ignored as peripheral to the main action revolving around Bligh and Macarthur, Johnston and Foveaux, and Government House Sydney on the 26th January.

The Hawkesbury’s local historians have devoted only a few pages to the Usurpation before moving quickly on to the glories of the Macquarie era. The most notable is probably Bowd, who in 1969 wrote that the Hawkesbury settlers were loyal supporters of Bligh, who promoted their welfare as the colony’s food producers. They disputed Macarthur’s right to make a welcome address to Bligh on their behalf, and drew up their own welcome. Bligh set a good price for purchasing their grain for the public stores, and the settlers publicly pledged their loyalty to his government. After the overthrow of Bligh, the settlers were forced to sign a petition of support for the Rebels, but most recanted as soon as they could and subsequently signed several petitions calling for Bligh’s restoration. Bowd noted that “It was well within the power of the ruling junta to bring ruin upon those who opposed them”, and cited the example of Martin Mason who was forced to sell his farm[4].

Elsewhere in his book Bowd also makes occasional references to the mixed fortunes of many during this period. William Cox was absent from the colony, and so “…free from the factionalism of the period…” which later made him eligible for appointment as Chief Magistrate in 1810; Richard Fitzgerald “…had the direction of Mr J MacArthur’s affairs …[and]… sided with the usurpers…”, and was appointed a magistrate during their regime; Andrew Thompson had “…made an implacable enemy of Macarthur…” and was dismissed from the magistracy during the Usurpation; Thomas Arndell, the first magistrate at the Hawkesbury, was a prominent supporter of Bligh; Archibald Bell “…was made a magistrate at the Hawkesbury by the rebel administration and was given a grant of 500 acres…”. The “…courage and forthrightness…” of Andrew Johnston at Portland Head was evidenced when he “…christened his youngest son James Bligh in 1809, when the rebels were in charge of the colony…”. William Singleton “…was a signatory to the various petitions that circulated during the Bligh period…”.

Two decades later in 1990 Powell & Banks included in their Hawkesbury River History an essay on the settler Peter Hibbs[5]. The author noted that during the Usurpation Hibbs was spared the foreclosures on loans suffered by many of Bligh’s supporters, and “…appears to have had two bob three ways…”, having signed petitions both supporting and opposing the Usurpers.

A cast of characters begins to emerge from these writings. Magistrates are being replaced; petitions of support and opposition are being signed – sometimes under duress; support for Bligh or the Usurpers is being demonstrated in various ways. Clearly, something is going on, and it seems to be of greater importance that a few drunken soldiers dragging a notoriously bad tempered viceroy from under his bed in Sydney. Several historians have acknowledged the hardships suffered by the Hawkesbury settlers, although not all of them have been kind. The two issues evident in the work of local historians, the replacement of the magistracy, and the settlers’ public petitioning, point to two themes in the ‘Rum Resistance’ as it was played out on the Hawkesbury stage that I will explore a little further.

So what was the ‘Rum Rebellion’?

But what was the Rum Rebellion? Briefly, the arrival of Governor-designate Bligh in August 1806 was warmly welcomed by the Hawkesbury settlers, and many in Sydney, but viewed with some suspicion by vested interests in the local military force, the NSW Corps, popularly known as the Rum Corps. This was confirmed by the first meeting between Bligh and the colony’s wealthiest man, and former Rum Corps officer, John Macarthur. They met in the garden of Government House Parramatta at a dinner hosted by retiring Governor King, and almost immediately quarrelled when Macarthur began pressing his claims for a large grant of land. It was a bad omen for the future.

Old Government House Parramatta, where Bligh and Macarthur first met in the viceregal gardens. Image NSW Heritage

Relations between the two parties deteriorated rapidly. In the absence of a political assembly, their conflicts were fought out in the local courts. By the summer of 1808 the political atmosphere was poisonous, and on the evening of the 26th January the officers of the Rum Corps under Major Johnstone and Lieutenant Bell marched on Government House Sydney where they seized the Governor and placed him under house arrest, declared a state of martial law to exist, and freed Macarthur from the Sydney jail where he was awaiting trial. He was carried by a drunken mob through the town. This has been variously described as a coup d’état, a rebellion, an uprising or an insurrection, although they usual description at the time was a usurpation (according to its opponents) or the overthrow of a tyrant (according to its supporters).

One of the first actions of the rebels was to isolate Bligh. Bligh wrote to Lord Castlereagh that “Every precaution was used by the rebels to prevent any communication with the interior of the Colony. Guards were set on the road to Parramatta, and no one suffered to pass.”[6] Bligh hoped that during the night he might be able to escape from Government House and flee to the Hawkesbury, where he could rally the settlers and other loyalists.[7] However, as he later told Castlereagh, “…the Settlers are in a very enraged state of Mind at the indignity I suffer through my arrest …[however] their want of Arms has prevented much bloodshed, and the precaution of disarming them…[some months earlier], whereby the Military became of greater power, has by this means acted against us, and enabled them to act with greater confidence”.[8]

The Usurpation lasted for nearly two years, covering almost the whole of 1808 and 1809. This period, sometimes called the interregnum or the rebel administration, has three distinct phases. The first lasted for six months under the command of Major Johnstone, with Macarthur as his Colonial Secretary; the second for nearly six months under the command of Colonel Foveaux; and the third for twelve months under Lt Col Patterson, although Foveaux appears to have held the reins of power during this phase as well. Each of these men occupied the office and used the title of Lieutenant Governor.

There were various fallings-out between the Usurpers, and their aims, never very clear or unified apart from hatred of Bligh, shifted and changed over time. Bligh was kept imprisoned in Government House Sydney until he agreed to leave for England in February 1809. This proved to be a ruse, and instead he sailed for Hobart, where he remained exiled on HMS Porpoise until he heard of Macquarie’s arrival and sailed back to Sydney. The Usurpation ended in fact when Macquarie arrived in the colony at the end of 1809, and officially on New Years Day 1810 when Macquarie assumed the office of Governor and revoked all the acts of the Usurpers.

An orthodox view of the rebellion: Raymond LIndsay’s 1928 painting of Major Johnson announcing the arrest of Bligh, depicted in the heroic style of liberators justly overthrowing a tyrant. Image HHT

While the Usurpers claimed to have rescued the colony from a tyrannical governor, Bligh and the loyalists invoked the language and imagery of the French Revolution to describe the Usurpers. Bligh asserted that a jubilant Macarthur crowed on the night of the overthrow that “Never was a revolution so completely affected, and with so much order and regularity”, and described Nicholas Bayly, the “…self-created Lieutenant-Governor’s Secretary …” coming to Government House “…and in a very Robesperian manner he read and delivered a paper to me…”.[9] It is a symbolism that was soon picked up by local songsters, perhaps most notably in ‘A New Song …On the Rebellion’, written sometime in 1808[10]. Some of its more notable lines are:

The voice of rebellion resounds o’er the Plain.

The Anarchist Junto have pulled down the banner

Which Monarchical Government sought but in vain

To hold as the rallying Standard of honor,

The Diadem’s here fled

From off the Kings head

And further on:

And the New Gallic School in its stead have erected,

John Bull’s would-be pupil, how dare he to frown

His French education was too long neglected.

That Turnip head tool

Jack Boddice’s fool.

And:

A clown in his gait, and a fool in his Face,

The Carmagnol Mayor

Has here got an heir.

‘Off the kings head’, ‘Gallic school’: some of the allusions seem obvious; other less-so. John Bull’s would be pupil and his neglected French education is an allusion to Foveaux’s French ancestry and the French revolution; Turnip Head refers to Johnston, Jack Boddice to Macarthur; the Carmagnole was a popular song and dance during the French revolution, and is an allusion to the first revolutionary Mayor of Paris, Jean Bailey, a principle in the execution of Louis XVI who was later guillotined himself, and thus a play on the name of Nicholas Bayly – the song writer noted of Bailey that “His hopeful namesake has been no less active in putting down monarchy here, being a Principal in the Rebellion now existing”. And while there were no appointments with Madame Guillotine on the Parade Ground in Sydney, the association of the Usurpers with violent revolution and the destruction of lawful authority was commonly made over the Cumberland Plain in such ‘pipes’.

‘Trying out the guillotine’, a French revolution cartoon showing Louise XVI about to be executed while revolutionaries make coarse remarks, seemingly unaware that they will soon meet the same fate. Bailly may be the fifth figure from the left, exclaiming ‘Paris has re-conquered its king’. Image UCL

The Right to Petition

The principle means by which we have some idea of the reactions to the Usurpation by the Hawkesbury settlers lie in the petitions and counter-petitions they drew up and signed.

Petitioning the King, and by extension anyone in authority, without fear of persecution was a long-recognised right. The settler’s petitions usually took the form of an address to someone in authority, with their welcome address to the newly arrived Bligh in 1806 the first in a series.

Fletcher analysed the four petitions from the Hawkesbury settlers of 22 September 1806, 29 January 1807, 25 February 1807 and 1 January 1808, which cover the period from Bligh’s arrival to the eve of the Usurpation. There are also two petitions of 17 February 1809 and 17 March 1809 during the Usurpation, and then another of 1 December 1810 after the first year of the Restoration under Macquarie.

Fletcher showed that about 75% of the Hawkesbury settlers had signed the pre-Usurpation petitions, included old and new settlers, large and small land holders, emancipists predominated numerically, but almost all of the free settlers had signed. The January 1808 petition had been broader, including some Parramatta and Sydney landowners, and about 30% of the signatories were not farmers but tradesmen and labourers. The Portland Head Presbyterians were consistent signatories. Thus, he concludes that the petitions are as representative of the settler’s views as we are ever likely to know. Fletcher also makes the point that, while signatories to a petition supporting the Usurpation were very soon afterwards renouncing their support and claiming their signatures had been obtained under duress, no such allegations were ever made by the pro-Bligh petitioners.[11] The signatories were mainly men, but a small proportion were women, presumably those who held land in their own right?

Evatt ascribes great importance to the petitions, describing them as a ‘Bill of Rights’. Their key demands were freedom of trade and an end to monopolies and extortion, justice to be administered by civil rather than military authority, and debts to be payable in currency rather than goods.[12]

The words of the petitions, in addition to these general points, can speak for themselves:

22 September 1806, with 244 signatures – Asked Bligh to protect the people in general in their rights, privileges, liberties and professions, as by law established; suffer the laws of the realm to take their due course; and that justice be administered by the Courts authorized by His Majesty, according to the known law of the land;

29 January 1807, 156 signatures – ‘We will be ready at all times, at the risk of our lives and property, lawfully to support our native laws and liberties under a just and benign government’;

25 February 1807, 546 signatures – ‘We have willingly enrolled our names for the defence of the country; and request that you dispose of rebellious ringleaders and principles to prevent future conspiracies and stop keeping liege subjects in constant alarm’;

1 January 1808, 833 signatures – ‘We hold ourselves bound, at the risque of our lives and properties, to support Your Excellency; we request freedom of trade, and trial by jury, and have confidence in your detailed research and knowledge of the whole country;

17 February 1809, 14 signatories “who came free into the colony” (mostly around Portland Head) – we abhor and detest the rebellion; the military continues to monopolise trade and land; there is favoratism, corruption and excessive punishments by the Officer-Judges; we remain loyal to Bligh; and pray for protection and relief from the rebels;

17 March 1809, 15 signatories “who came free into the colony” (mostly around Portland Head) – we fear our houses being assailed, our wives and daughters violated, our property plundered; the government is corrupt at all levels; we were forced to sign an address of support for Johnston under fear and terror; bands of soldiers and abandoned and worthless characters are intimidating settlers and burning effigies of Your Excellency; drunkenness is everywhere; we need speedy protection and relief’

1 December 1810, 94 signatures – congratulate Macquarie on his arrival; and give thanks for the appointment of William Cox as a local magistrate – to which Macquarie thanked them, and advised that he had fixed on the sites for the new towns.

Freedom of trade, trial by jury and judicial fairness are central to the earlier petitions, as well as expressions of loyalty to Bligh. The settlers petitioning against monopolies indicates this remained a real issue for them, although recently the journalist Michael Duffy[13] and historian Peter Cochrane[14] have both claimed the monopoly problems had been overcome, especially in the rum trade,[15] and Chief Justice Spigelman also seems to have taken a similar view in his Australia Day Address last week[16]

The two petitions prepared in 1809 are markedly different, being signed only by the free settlers, stating the terror there are living under, and seeking help. They were also made and sent to Bligh after he had left Government House Sydney, perhaps in the hope that the Usurpers did not control Hobart and he could get help. The petition of 1810 marks the post-rebellion settlement: a new untainted magistracy and new towns above the floodwaters.

The Terror in the Hawkesbury

Petitioning, however, did have its consequences. The Usurpers could not let the settler’s constant challenges to their pretended authority go unnoticed, especially when they had so boldly and publicly signed their names to every petition, and published the pre-usurpation petitions in the Sydney Gazette for all to see.

The changes in the magistracy noted by Bowd are important, for the magistrates of this period not only presided over the local courts. They were also the agents of the civil government. They were often consulted collectively by the governor of the day, forming a sort of privy council. The replacement of Arndell by Bell symbolised the power of the Usurpers, further reinforced by Bell’s known alignment with Macarthur’s ‘Exclusive’ faction (Thompson was an emancipist), and the granting of land to him that included Richmond Hill, the highest point in the district, again symbolically bringing the whole district under the gaze of the Usurpers, reinforced their ‘Exclusive’ approach to governance. The replacement of Thompson (an emancipist) with Fitzgerald (an emancipist sympathetic to the rebels) strengthened their hand.

Under the governments of Bligh and King, the Hawkesbury settlers has a role in the governance of their district through their control on the local Commons trusts, and in the colony through the inclusion of their magistrates in the vice regal ‘privy council’. Government House at Green Hills had been the centre of public authority since the mid-1790s, and during the Usurpation it was the local command centre for their administration under Commandant Bell and the new magistracy. It was a place where proclamations and orders were issued, musters were organised and sometimes held, official business was transacted, and official functions held. It was the seat of government in the district.

Bligh had his own large property near Pitt Town named ‘Blighton’, which was operated as a model farm, intended to demonstrate to the settlers new methods of agriculture to help improve their farming practices. Bligh’s Overseer, Andrew Thompson, wrote in 1807 of Bligh’s “…wisdom and attention to farming and improvement, which the Sovereign was pleased to practice at Home, … as an example to all others…”[17]. It was a practical contribution to supporting the local settlers, and something of a cause célèbre for the Usurpers, who claimed the farm was evidence of Bligh’s corruption as he used public resources, such as convicts, livestock and stores at the Crown’s expense for his private gain[18]. It stood as a symbol of the resistance, a model of orderly, productive husbandry in the community, in stark contrast to the illegality and repression that emanated from the rebel-controlled Government House.

Sketch map showing the location of ‘Blighton’ (upper right) in the Hawkesbury District. Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. VI (1898).

The Usurpers were well known by their redcoat uniforms, their use of the Union flag and Royal Arms, and their too-frequent toasts and shouts of God Save the King. Their use of the Public Seal, with its depiction of convicts landing at Sydney Cove, was limited – party because Bligh had managed to sequester the Public Seal to prevent its capture by the Usurpers until they forced him to reveal its location, but also because the promise of convict redemption alluded to in its design was anathema to the Exclusives among the Usurpers. Bligh issued a proclamation from his exile in Hobart which states in part “That I only am empowered to keep and use the public seal for sealing all things whatsoever [in] the territory and its dependencies”.[19] The hijacked symbols of Royal authority failed to impart the legitimacy the Usurpers craved.

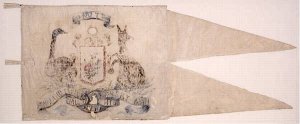

The resisters also had their symbols, the most notable (I believe) being the ‘Bowman Flag’. The flag, made by the women of the Bowman household, shows a shield with the entwined rose, shamrock and thistle of England, Ireland and Scotland, supported by a kangaroo and emu, with two motto ribbons: the upper reading ‘Unity’, and the lower Nelson’s great signal at Trafalgar ‘England Expects Every Man to do His Duty’. On one level, the flag celebrates Nelson’s victory. The news had reached New South Wales in April 1806, six months after the battle[20]. It was four months before Bligh’s arrival, but already the tensions that would lead to the Usurpation were building up. In the context of the Usurpation, the flag takes on a different meaning.

The Bowman Flag, symbol of the Hawkesbury Resistance. Image NSW Heritage

Nelson was a naval hero and true patriot who fought for his king and country, unlike the Usurpers who overthrown the duly appointed governor for their own personal ends. Unity amongst the settlers was vital if they were to resist the rebels, as it was their duty to do. The intertwined floral emblems suggest the mixing of nationalities among the settlers, and placed upon a shield further suggests that this diversity gave them strength, just as the recent union of England, Scotland and Ireland had created a newer, greater Britain that Nelson had defended. The kangaroo and emu supporters, their heads turned warily over their shoulders, indicate the new country into which the settlers were putting their roots, and were ready to defend. The flag invokes the settler’s loyalty to resist the Usurpers, its imagery patriotic without being obviously subversive.

Thus our stage has been furnished: the scenes of good and bad have been painted, the building props set up, and all embellished by the contested heraldry of reds, whites and blues. Now its time for the actors to make their entrances and exits.

The main leaders of the Hawkesbury settlers, going by the principle signatories on the various petitions and the work of Brian Fletcher, were Andrew Thompson, Thomas Arndell, George Crossley, Martin Mason, John Bowman, William Cummings and Thomas Matcham Pitt. In Sydney, Robert Campbell, John Palmer and William Gore were prominent supporters of Bligh; as was George Suttor at Baulkham Hills. Fletcher states that after leaders such as Thompson and Crossley had been silenced under Johnston, settlers such as Mason and Suttor took over the leadership of the loyalists.[21] I have not yet identified any Norfolk or Vandemonian leaders, but note that Lieutenant Governor Collins in Hobart issued an Order in April 1809 prohibiting the newly arrived Norfolk settlers “..and other persons…” from addressing letters and petitions to Bligh while he was in the town, on pain of being bought before a magistrate to answer for their actions.[22] Presumably the addressees were leaders in their communities, and were approaching Bligh for a reason.

A brief look at how some of the Hawkesbury leaders fared during the Usurpation is illustrative of the repressive nature of the rebel administrations.

Thomas Arndell, English free settler who married his convict wife Elizabeth in 1807, was a resident magistrate appointed at the Hawkesbury by 1802. During the usurpation, he was dismissed from the magistracy, and his pension was discontinued without explanation. In 1809 he wrote to Viscount Castlereagh, praising Bligh and stating that he had been forced to sign a petition following the Usurpation supporting Johnston, and that “…artifice and threats” and been used to force the “…frighted inhabitants” to sign the same petition. Macquarie restored his pension in 1810.[23]

Andrew Thompson, Scottish emancipist, was appointed a constable in 1796 and succeeded Thomas Rickaby as Chief Constable in 1804, a Trustee of the Nelson (Pitt Town) and Richmond (Ham) Commons in 1805, shipbuilder, store and inn keeper, farmer and brewer, overseer of Bligh’s model farm; he was dismissed as Chief Constable during the Usurpation under Johnston, although he later received grants of land in Sydney under Foveaux and at Minto under Paterson; appointed by Macquarie as a magistrate, he was the first emancipist to hold this office.[24]

George Crossley, English emancipist, a lawyer, acquired a farm at the Hawkesbury in 1801, acted as a legal advisor to the Provost-Marshall and the Judge-Advocate, and to governors King and Bligh, although he was prevented from formally working as a lawyer because of his conviction; he helped the Judge-Advocate prepare a case against Macarthur, and was at Government House Sydney advising Bligh on his correspondence when the rebels surrounded the House and captured Bligh; he may have been the author of some of the Hawkesbury petitions; he was arrested by the rebels, and tried by them for practising as an attorney, convicted and sentenced to 7 years transportation to Coal River.

Bligh gave his version of Crossley’s trial: “McArthur used every endeavour to win over Mr George Crossley to assist him … but when [he] found that he could have no influence over Crossley, he endeavoured to injure him, first by attributing to him such situations as he did not hold; and secondly, by his influence over the Military Officers, procuring a Sentence of Transportation to the Coal-Mines for seven years against him for giving his assistance to the Government”.[25]

Macquarie released Crossley from the mines, and when he petitioned the new Governor for compensation he stated that he had “retired to his farm at the Hawkesbury [and would]…endeavour to recover from the ruin in which he is now involved …humanity cannot compensate for your memorialist’s two years’ imprisonment in the sixty third year of his life, but it is in Your Excellency’s power to assist him to forget that past by extending to him your protection, advice and assistance…”. Crossley was allowed to sue the rebels that sat in the court which convicted him, and was awarded £500. However, he was unable to practice as a lawyer again, despite several attempts to do so.[26]

Martin Mason, English surgeon and free settler, farmer at South Creek, was forced to sell his farm in 1809 after publicly stating that he was prepared to take a settlers address to England to present Bligh’s case. Gore wrote to Viscount Castlereagh in 1809, nominating Mason as an illustration of the lawless state of the colony under the rebels. Mason had been apprehended on the road to Parramatta “…by men armed with naked cutlasses…”, and taken before the Commandant at that town “…who grossly insulted and examined him on the subject of a letter…” Mason was writing to Castlereagh. He was then taken to Sydney, where he was examined by ‘rebel justices’ “…as to his motives for writing the intercepted letter…”. The letter was detained by Paterson and its contents suppressed, indicating how the loyalists were being “..persecuted with unrelenting severity”. Gore asked Castlereagh to forgive the badness of his writing, as in avoiding the “…miscreant traytors …[and] revolutionary partisans…”, he had had to write“…in the woods … by stealth and piecemeal”.[27]

John Bowman, Scottish free settler, farmer at the Hawkesbury since 1798, Trustee of Richmond (Ham) Common in 1805; sued by Nicholas Bayly in 1808 for calling him a rogue, he was imprisoned, and in 1809 his property was seized and auctioned by Bayly as Provost-Marshall. This apparently destroyed his financial security, and in 1813, long after the Usurpation had ended, he had to sell most of his property to pay further debts. The settlers petitioned Viscount Castlereagh in 1809 to show that they had no hand or part in the Usurpation, and mentioned Bowman’s case as an example of excessive punishments meted out by corrupt rebel judges: “When your memorialists applyed for protection they are frequently treated with insult, and if they presumed to appeal to the [rebel Lt Governor] they are liable to be dragged to prison by convicts and locked up without meat, drink, fire or candle, or even straw to lye on, with the most abandoned thieves. [John Bowman] was locked up in the same cell with three malefactors under sentenced of death, tried, fined, and imprisoned without being taken before a magistrate, remanded, and again confined with the above malefactors. His offence was unguardedly saying that Nicholas Bayly was a rogue in recommending and promising to support his (Bowman’s) servant in prosecuting his master for false imprisonment … tho’ the servant had acknowledged his [original] offence”.[28]

Thomas Matcham Pitt, English free settler and relative of Lord Nelson, farmer at the Hawkesbury since 1802.[29] Pitt is the only one of the resistance leaders who does not seem to have suffered any retaliation – perhaps his connections with Lord Nelson protected him?

These individual biographies reflect the language and methods employed by the Usurpers to break the resistance. One response to this persecution, symbolic in its application but with real consequences, was refusal by the loyalists to acknowledge the legitimacy of the rebel courts.

In March 1808, Provost-Marshall Gore, whose office Nicholas Bayly had now usurped, was tried for perjury. His response to the charge was an emphatic “I will not plead; I deny your jurisdiction”. The rebel magistrates sentenced him to be transported for seven years to Coal River, to which Gore responded: “You have conferred on me the greatest Honor you are capable of conferring, the only Honor I could receive from such Men. Loyalty and Treason could not unite”.[30] Similarly, a charge against George Sutter of seditious libel was met with Sutter declaring “I deny the legality of this Court; you may do with myself as you please”, for which he was sentenced to 6 months imprisonment and a fine of one shilling.[31]. A similar case of seditious libel against John Palmer and Charles Hook was met with a similar refusal to plea, and they were fined £50 and imprisoned for three months.[32]

It also appears that Bligh was not the passive recipient of the settler’s adoration. By the spring of 1808 Foveaux was complaining that Bligh “…was exerting every means in his power to inflame the minds of the settlers by sending emissaries among them, who promised in his name that in the event of his restoration to the Government he would make them rich and happy. I thought it my duty to inform him that if he persevered … I would send him to England … [and] remove him from Government House and be obliged to impose additional restraint on his person…”.[33] Foveaux later tried again to remove Bligh to Government House Parramatta, but he again refused to budge.[34]

The botanist George Caley visited Bligh in October 1808, and described the repressive atmosphere inside Government House Sydney: “Meeting him [Bligh] in the hall, expressing as he went into the parlor, “You see how they have served me; they might have well as done the same to the King of England.” Having shut the door, he desired me to sit down in a corner of the room, where I perceived the sentinels could not see me. He began his discourse (which was mostly whispered) by wishing me to write to you [Banks]. … I conceived [this] of but little use, for I was strongly persuaded by my own mind that the letters would be intercepted [as both ships in the harbour were under Macarthur’s control]. … about the conduct of Lieu’t-Gov’r Foveaux – as he styles himself …When he had the command of Norfolk island he was spoken of as a very severe man, but here at present it evidently appears he is aiming at becoming popular. But what is the use of the popularity of convicts? … he is acting a very sly, cunning part.”[35]

Government House Sydney floor plan in 1808: note the parlour where Bligh and Caley met, on the right. Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. VI (1898)

The Terror elsewhere – Baulkham Hills and Norfolk Island

The settlers around Baulkham Hills tended to support those at the Hawkesbury, notably George Suttor, a free settler who had been farming at Baulkham Hills since 1802. Bligh had promised him another land grant, but the overthrow prevented the grant being made. Suttor was a leader of the settlers, and selected to go to London with Mason in 1808. He refused to attend a muster being held by the rebels, and was ordered to court in Parramatta, then taken to Sydney. While he was away, five convicts were sent to his house, he claimed by Foveaux, where they abused his wife, and drove away his cattle. Suttor had to give them two bottles of wine to get the cattle returned. The next week he was jailed for six months, as were four others men who had refused to muster, including Martin Mason.[36] Like the refusal to recognise the jurisdiction of the rebel courts, the refusal to attend musters was another form of resistance employed by the loyalist settlers.

The situation on Norfolk Island during the usurpation is unclear. The British authorities were prevaricating between closing the island and keeping it open. Foveaux had returned to Sydney in 1807 with instructions to maintain the settlements, but by August 1808 had commissioned the ‘City of Edinburgh’, through Macarthur, to evacuate half the population to Hobart.[37] The majority of the Islanders did not want to leave, some of them having spent 20 years establishing their farms and families, and they had no great love for Foveaux who had been Commandant on the island between 1800 and 1804.[38] Nevertheless, 224 settlers and all their possessions and livestock were removed from the Island in September, arriving in Hobart on the 2nd October. Lt Governor Collins reported to Foveaux that the voyage had been longer than expected, provisions were running low, and “Several of the settlers complaining, some that their property had been plundered on the voyage, others that it was not forthcoming”.[39] Collins directed the magistrates to investigate, and their report seems unsurprising: while much property had gone missing, they were unable to fix responsibility on any individual. Bligh wrote later that same month “Concerning the poor settlers of Norfolk Island”. The evacuation had not been approved by him, and the ‘City of Edinburgh’ was “…the infamous ship which sold and distributed her liquors to McArthur and his emissaries at the time of the insurrection”.[40]

Collapse and Restoration

By the end of 1809 the Usurpation had dragged on for two years. The initial excitement had long dissipated and been replaced, for the loyalist settlers at the Hawkesbury and elsewhere, by sullen acceptance punctuated by acts of civil disobedience such as not attending musters or denying the authority of rebel courts, petitioning for the restoration of Bligh, and managing their farms as best they could. They, like Bligh, new that eventually relief would arrive from England and, like Bligh, they firmly believed that the lawful order would be restored.

On the 28th December 1809 Major Lachlan Macquarie and the 73rd Regiment sailed into Sydney Harbour. The Regiment landed on the 31st December, and on the following New Years Day Macquarie issued the proclamations and orders by which he took control of the colony.[41] There was no resistance from the Rum Corps or Paterson’s administration. Macquarie reported that on his arrival he had “…found the colony in a state of perfect tranquillity, but in a great degree of anxiety for the long expected arrival of a new Governor.”[42]

He found the public stores almost empty, and the hoped-for harvest from the Hawkesbury destroyed in the flood of August 1809; the public buildings in a state of decay; and Bligh exiled in Hobart. Within the first week of his government, Macquarie undid all that could be undone of the rebel administration: all public appointments were declared invalid, and the former officials were restored to their offices; all land grants and leases were declared null and void; all trials and investigations were declared invalid; all official papers and records were to be returned to Government House within one week; all grants and leases were revoked, specifically including grants to soldiers. However, by another proclamation he prohibited the settlers from taking actions against rebel officials unless they had committed illegal acts of oppression and injustice, and called upon the inhabitants to demonstrate “…forbearance, and the importance of that union, tranquillity and harmony in the present crisis” rather than “…the constant recourse to a vexatious and obstinate system of litigation”. Wrongs would be righted, but there would be no general retaliation and purging of the Usurpers.

Macquarie made it a priority to visit the Hawkesbury, and already had formulated a plan for relocating the settlements to high ground. But that’s another story, suffice to note that of the five towns he established in the district, three he named after Whig reformers, although two are now remembered as Tories. Wilberforce was named after the great anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce, Castlereagh commemorated Viscount Castlereagh, Colonial Secretary, now remembered as a reactionary but at that still committed to Catholic emancipation and parliamentary reform, Pitt Town recalled Britain’s first prime minister who supported parliamentary reform, Catholic emancipation and abolition of the slave trade, and was also a friend of Wilberforce and patron of Castlereagh. Pitt and Castlereagh were key figures in the union of Great Britain with Ireland in 1801, which they believed would overcome sectarian differences, and in the wars with revolutionary and then Napoleonic France. I think the names were intended as a tribute to the beliefs the settlers had stood for in their resistance to the Usurpation: the rule of law, progress through reform, resistance to arbitrary rule, and freedom of trade and commerce.

Bligh did not hear of Macquarie’s arrival for some days, and it took him nearly three weeks to get back to Sydney. He landed in Sydney Cove in the afternoon of the 17th January “…to the great satisfaction of the people, expressed by their cheering…” he later wrote to Castlereagh.[43] Bligh spent the next few months in Sydney, gathering evidence for the trials of the Usurpers in England, finally leaving on the 12th May. The Hawkesbury settlers do not seem to have drawn up an address of farewell.

Legacies

I began with some questions to which some answers can now be attempted.

Who were the Hawkesbury settlers? Fletcher probably answered this question in 1968. They comprised most of the landholders in the district, emancipist and free, as well as some of the small business people. Fletcher considered they were a representative cross-section of the community, concluding that on “…a balance of probability … there was strong support for Bligh at the Hawkesbury”.

How did the settlers show their support for Bligh? Their petitions are the obvious answer, and they have been the main evidence cited since 1811 and earlier. However, there are other ways: ‘Blighton’ is associated with their support for Bligh and the royal authority he represented (remember Thompson’s analogy with King George, who was also known as ‘Farmer George’); and the Bowman Flag can be read as the real symbol of their resistance to the Usurpers.

How did the settlers resist the Usurpers? Firstly, we have two waves of their leaders, all prepared to publicly engage with the rebel regimes, often a great personal cost. The tactics of civil disobedience were employed in denying the legitimacy of the rebel courts, and in refusing to attend musters held by the rebel magistrates, again at great personal cost. There were also visits to the detained Bligh, often under a cloak of subterfuge; and the surreptitious writing of letters to authorities in England telling them of what was happening. And there were the ‘pipes’ such as A New Song … of the Rebellion, softy but surely subverting rebel authority.

What did their loyalty cost the settlers? For the leaders, the costs included fines, foreclosures, imprisonment and transportation to Coal River; while their supporters endured abuse and humiliation from the soldiery and packs of convict ‘let off the stores’, theft of their property, a general failure of law and order, and sights such as the drunken burning of effigies that reminded them of the excesses of the French Revolution, and made the men fear for the safety of their womenfolk.

By the time of the Restoration under Macquarie two years of the rebel regime had been endured. There could have been a viscous counter-revolution, and may well have been had Bligh still been in Sydney. However, Macquarie brought with him a policy of reconciliation, and was able to have this in place by the time Bligh returned from Hobart. His most notable example was the rehabilitation of Foveaux, something that Bligh could neither understand nor stomach and, I suspect, neither could the settlers. However, worn down by the long Usurpation, and once again devastated by floods, I suspect that their relief at the Restoration overcame much of the accumulated bitterness.

The local histories now speak warmly of the Bells and Fitzgeralds, with no reference to the bitter circumstances in which these families were planted in the Hawkesbury. Little mention is made of the dark days of the usurpation. The effects of Macquarie’s policy of reconciliation appear to have lasted long into the present day. In this sense, the Hawkesbury is probably a microcosm of the healing that had to take place in Sydney and Parramatta, Norfolk Island and Van Diemen’s Land, even at the Coal River. Perhaps it has worked so well that today we are not really sure of the importance of the rebellion to our history as Australians?

In their resistance, the settlers reflected a tradition of actively building a better or new society in English history through ‘parliamentary’ means, not violence, which itself had developed as a response to several centuries of civil wars and Saxon/Celtic and Catholic/Protestant conflicts. Other ways had to be developed to effect social and political change, and were sealed in the compact of the Glorious Revolution only 120 years before. It was part of the ‘invisible baggage’ they brought with them to New South Wales, that distant maritime country on the far side of the globe, and which is also part of our history. It was Usurpers who were the reactionaries, contrary to the loyalists use of allusions to the French Revolution.

To oppose a tyrannical or unjust government is the right thing to do. That is what a commoner or citizen does. The actions of the Hawkesbury (and other) settlers, especially under the ‘second wave’ of leaders such as Suttor and Mason, and the Portland Head Presbyterians, demonstrated their claims to be morally and legally right, and ultimately it was their resistance that was vindicated, not the usurpation.

The Rum Rebellion was not just a colourful colonial curiosity. We have had no military coups, no civil wars, since that time. We can reflect on this Australia Day, and on this bicentenary of the Usurpation, that we should in no small measure give thanks to the Hawkesbury settlers and their courageous resistance for what Macquarie might have called “…the importance of that union, tranquillity and harmony” in our Commonwealth today.

The signature of Governor Lachlan Macquarie: symbol of the Restoration. Image SRNSW

[1] Title taken from ‘Address of Hawkesbury Settlers to Bligh’, 29th January 1807, in Historical Records of New South Wales, Volume VI, Government Printer, Sydney 1898: 237

[2] Evatt, HV., Rum Rebellion: a study of the overthrow of Governor Bligh by John Macarthur and the New South Wales Rum Corps, Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1938

[3]Fletcher, B., ‘The Hawkesbury Settlers and the Rum Rebellion’, in Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 54, Pt 3, 1968: 217-237

[4] Bowd, D.G., Macquarie Country: a history of the Hawkesbury, the author, Netley SA 1969: 8-10.

[5] Wilson, E., & Richmond, T., ‘The Saga of Peter Hibbs’, in Powell, J. & Banks, L. (eds), Hawkesbury River History: Governor Phillip, exploration and early settlement, Dharug & Lower Hawkesbury Historical Society, Wisemans Ferry 1990: 91

[6] Bligh to Castlereagh, 30 April 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 432

[7] Evatt, op. cit.: 141-142

[8] Bligh to Castlereagh, 30 April 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 438

[9] Bligh to Castlereagh, 30 April 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 431, 435

[10] Mackaness, G., (ed), A New Song, made in New South Wales on the Rebellion, by Lawrence Davoren, Edited with an Essay on Historical Detection, Notes and Commentary, Review Publications, Dubbo 1979

[11] Fletcher 1968, op. cit; 230

[12] Evatt, op. cit: 69-71

[13] Duffy, M., ‘Captain Bligh’s Other Mutiny’, Sydney Morning Herald, 19-20 January 2008: 34

[14] Cochrane, P., ‘Bligh’s Bounty of Disputes: Review of the Week: “Captain Bligh’s Other Mutiny”’, by Stephen Dando-Collins, Sydney Morning Herald, 29-30 December 2007: 27

[16] Spigelman, J., ‘Coup that paved the way for our attention to the rule of law’, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 January 2008.

[17] Thompson to Bligh, 26 March 1807, HRNSW, Vol VI: 263

[18] Fletcher, 1968: 220

[19] Proclamation, 29 April 1809, HRNSW, Vol. VII: 109

[20] Huxley, J., ‘Going Into Battle for Nelson’, Sydney Morning Herald, 20 October 2005: 11

[21] Fletcher 1968, op. cit.; 231

[22] General Order, 25 April 1809, HRNSW, Vol VII: 101

[23] Fletcher, BH, ‘Arndell, Thomas (1753 – 1821)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, Melbourne University Press, 1966: 27-28; Arndell to Castlereagh, 7 February 1809, HRNSW, Vol VII: 19-20.

[24] Byrnes, JV, ‘Thompson, Andrew (1773? – 1810)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, Melbourne University Press, 1967: 519-521.

[25] Bligh to Castlereagh, 30 April 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 427

[26] Allars, KG, ‘Crossley, George (1749 – 1823)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, Melbourne University Press, 1966: 262-263; Fletcher 1968, op. cit.; Crossley to Macquarie, 15 February 1810, HRNSW, Vol. VII: 288-289

[27] Bowd, op. cit.: 10; Gore to Castlereagh, 25 March 1809, HRNSW, Vol VII: 90-93

[28] Fletcher, BH, ‘Bowman, John (1763 – 1825)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, Melbourne University Press, 1966: 138-139; Settler’s memorial to Castereagh, 17 February 1809, HRNSW, Vol VII: 33-34

[29] Walsh, GP, ‘Pitt, George Matcham (1814 – 1896)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, Melbourne University Press, 1974: 446-447; Bowd, op. cit.,: 135.

[30] R. v. Gore, Court of Criminal Jurisdiction, Grimes AJA, 21 March 1808, Decisions of the Superior Courts of NSW, 1788-1899, http://www.law.mq.edu.au/scnsw/html/CoupagainstBligh.htm, accessed 25 January 2008

[31] R. v. Suttor, Court of Criminal Jurisdiction, Kemp AJA, 8 December 1808, op. cit.

[32] R. v. Palmer, R. v. Hook, Bench of Magistrates, 18 March 1809, op. cit.

[33] Fouveaux to Cooke, 21 October 1808, HRNSW, Vol VI: 783-784.

[34] Foveaux to Paterson, 27 October 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 786; Bligh to Castlereagh, 28 October 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 789

[35] Caley to Banks, 28 October 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 795-799

[36] Suttor to Bligh, 1 January 1809, HRNS, Vol. VII: 1-4

[37] Foveaux to Cooke, 21 October 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 784

[38] Hoare, xxx; Britts, MG, The Commandants: the tyrants who ruled Norfolk Island, KAPAK Publishing, Norfolk Island 1980: 48-58

[39] Collins to Foveaux, 23 October 1808, HRNSW, Vol VI: 785, and footnote

[40] Bligh to Castlereagh, 28 October 1808, HRNSW, Vol. VI: 788; also Bligh to Castlereagh, 30 April 1808, HRNSW, Vol VI: 424

[41] Proclamation, General Orders, HRNSW, Vol. VII: 252-254.

[42] Macquarie to Castlereagh, 8 March 1810, HRNSW, Vol. VII: 303

[43] Bligh to Castlereagh, 9 March 1810, HRNSW, Vol. VII: 309

Thank you – very interesting, and pretty convincing. I’m sure the rebels thought, with all their references to Tyrant and Tyranny, that they were following John Locke and therefore on the right side of the Glorious Revolution. But as in most rebellions, they quickly devolved into petty bullies, fighting amongst themselves.

Do you know how and where the Bowman Flag was flown?

LikeLike

I think this a really fascinating period that deserves a lot more study – glad you liked it. The best source about the flag is here http://acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/search/itemDetailPaged.cgi?itemID=446335, also here http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/discover_collections/history_nation/terra_australis/bowman/index.html, and here http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/Heritage/research/heraldry/bowmanflag.htm. As you will see there are several interpretations of what the flag represents.

LikeLike

[…] historian Bruce Baskerville has noted, Bligh’s downfall ‘has been variously described as a coup d’état, a […]

LikeLike